How to Make a

Storyboard and Shot List

Some DVDs (Shrek and The Matrix, for example) now include

sample storyboards shot-by-shot sketches drawn to visualize the action of key

sequences as bonus material. As you study these slick drawings, you'll notice

that most frames are remarkably close to the actual shots they predict. Back in

Hollywood's glory days, most directors (with Hitchcock a notable exception)

rarely worked with storyboards; today, however, they're everywhere. Once you

know how to make a storyboard you'll use them too. We'll start with a look at

what storyboards do.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

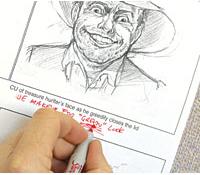

Figure 1a |

Figure 1b |

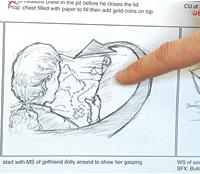

Figure 2a |

Figure 2a |

Figure 2a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2b |

Figure 2c |

|

|

|

Storyboards Visualize

Basically, pre-designed storyboards in pencil or marker predict what shots will

look like. Why not just invent shots as you actually shoot? Here are three

reasons.

First, storyboards let you test complicated setups

cheaply on paper instead of expensively on location. Suppose your script says,

"She unrolls the treasure map before her and she gasps as she sees where

the gold is buried." But when you draw a high-angle insert of the

unfolding map, you realize there's no way to get "she" into the frame

(Figure 1a). So you try a new angle: over her shoulder (Figure 1b). By moving

the camcorder to center her face and refocusing as she turns into profile, you

can get both her relation to the map and her reaction to it; and you haven't

wasted half an hour on a setup you'd eventually discard.

Secondly, you can check your coverage of a sequence and

preplan your video camera angles for variety, continuity and rhythm. Suppose

you sketch three shots of the male talent digging up the treasure chest (Figure

2a). Hmmm: though the sketches are from different viewpoints, they're all

neutral-height medium shots and are too repetitive. OK, substitute a

point-of-view (POV) closeup of the emerging chest (Figure 2b) and change the

last shot to a low-angle closeup of his greedy expression as he reacts to the

chest (Figure 2c). In 10 minutes of doodling, you've improved a sequence from

ho-hum to dynamic.

Storyboard Vision

So far, you've learned how to make a storyboard for your own use, but

storyboards also communicate your vision to others. Verbalizing image ideas is

always chancy, so it's better to show what you have in mind visually.

In the professional world, storyboards are essential for

communicating with clients, first to pitch concepts and then to preview the

live action. Never forget that visual imagination is like a sense of humor:

many people lack it, but no one will ever admit it. The client may nod and

smile as you verbalize your vision, but yelp, "You never said you'd do

that!" upon seeing the footage, even if that was precisely what you

promised. Prevent that scenario by putting your idea into sketches instead of

words.

Incidentally, you should have a professional artist draw

storyboards for clients. Even though you were hired to shoot, not draw, your

amateur scribbles will likely cast doubts on your professionalism. (Hey,

whoever said it was fair?) If you don't have a client to impress, don't worry

about the quality of your thumbnail sketches. As long as they communicate to

yourself and your crew, they do the job. There are two ways to do storyboarding

nowadays, either draw them on paper or build them on a computer.

Paper and Pencil

To make a board from scratch, draw between six and 12 rectangles on a virtual

sheet of paper (any word processor or paint program'll do it for you). Make the

horizontal/vertical ratio 4 to 3 (4:3) for conventional video or 16:9 for wide

screen. Leave enough space to write under each frame. Some people pre-print "Frame

#," "action," "audio," etc., but you don't have to be

that formal. Print out a large quantity of these blank boards.

Using simple lines and stick-figure subjects, sketch each

setup in a frame, observing just a few conventions. Indicate subject movement

with arrows in the frame. Show zooms by sketching the wide-angle position,

drawing a box around the telephoto position within it and adding diagonal

arrows to show whether the movement is in or out. For pans or tilts between two

distinct compositions, show each one as a separate frame, with an arrow between

frames to link them.

The notes that are written below each frame should

contain some or all of the following:

·

Frame number

·

Sequence ("27") or sequence and shot ("27B)

·

Action ("John runs past; then he exits frame right")

·

Camera instructions: ("No pan")

·

Dialogue: ("JOHN: Come back here with that map!")

·

Other audio: ("SFX: bullet ricochet")

·

Visual effects: ("Use bluescreen for the ship

composite")

Computer Boards

If you're deft with a mouse (or are fortunate enough to own a pad and stylus),

you can sketch boards directly on your screen. Perhaps the easiest way to do

this is with the draw tools in Corel Presentations or Microsoft PowerPoint.

This approach makes frames easy to add, insert, delete or modify.

A second method is to make individual sketches in the

draw/paint software you favor, then use a graphics organizer to print them as

sequential thumbnails. The ThumbsPlus software lets you add extensive notes

under each image.

A third route is a publishing package like Adobe

PageMaker. You can build a template page of blank frames, then either draw in

each one or import an outside graphic or even location photo.

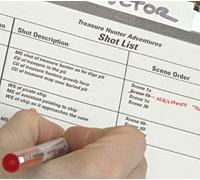

Shot Lists

Think of a shot list as the writing on a storyboard, without the pictures.

Though simple lists of shots don't let you pre-test potential setups, they do

allow you to systematically verify that you are covering every angle you need.

Often shot lists are just quick and dirty notes that help

you remember everything you need in a particular sequence. You can also cull a

shot list from a fully-written script if you separate the video into separate

columns (or separate paragraphs).